“I don’t think we should make our decisions based on doing what’s easy.”

I was born with Amniotic Band Syndrome, leaving me with a visible disability and without any function in my right hand. Sports became a mainstay of my childhood when I began playing soccer at the age of four. From there, I played basketball, volleyball, softball, hockey, and even tried taekwondo before I started throwing shot put in 2015. In each of these sports, I faced a variety of challenges, some that I never expected to face: Is it possible to play volleyball with one hand? How would I hold a hockey stick? Will I ever be a great athlete, or will I just be “pretty good for a girl with one hand?” These are some of the questions I’ve asked myself throughout my life as I learned to play any sport I found an interest in. Asking these questions was hard–but sometimes, learning how to do things differently as a disabled person was even harder.

Becoming involved in track and field wasn’t on my radar. I knew I didn’t enjoy running, so I never gave the sport any thought until a new friend found herself nervous to join our school’s track and field team. She was a new student at my school, and we had quickly become friends. I knew she’d been an outstanding track and field athlete at her old school, but now, surrounded by strangers, she felt nervous to go to the first practice alone. So I told her that I would go with her.

This was the beginning of my career as a thrower. In eighth grade and high school, I threw shot put and discus. I qualified for the state meet all four years of my high school career, and had mixed results: I was dealing with a lot of performance anxiety that seemed to be at its worst during high pressure meets. I also felt the pressure of how much harder I had to work to keep up with able-bodied competitors, and to overcome my own insecurities about my athletic abilities. But I loved the challenge of training as a thrower, and was thrilled to be recruited by DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois–a Division One university where I would be able to keep playing the sport I loved while I earned a degree.

At DePaul, I found my identity as an athlete, but not without struggle. My competition results were significantly worse than my teammates’ during my freshman year, and I found myself being left off travel rosters for meets. I was discouraged; I went to DePaul to keep competing in track and field, and I wasn’t good enough to go to the meets. When I didn’t make the roster for the biggest meet of my freshman season, I knew I had a decision to make: I could accept that I just wasn’t as skilled as my teammates, or I could work even harder and become good enough to earn my spot at meets.

I began taking my career more seriously than I ever had by pushing myself even harder in the weight room and taking even more reps at practice. With enough sweat and effort, I finally started throwing farther and traveling to meets. I was comfortable in my role within our team, and most of all, I was having fun again. And that’s when my coach asked me if I had ever considered joining the Paralympics.

At this point, I had lived all twenty years of my life as a person with a physical disability. Despite knowing this, I never truly identified with it. I tried to work so hard that no one would ever notice my disability. I tried to forget that I was disabled. If I competed in the Paralympics, I knew that I would have to come to terms with my identity as a disabled athlete, and all the unique grit, difficulties, and assumptions that come along with it.

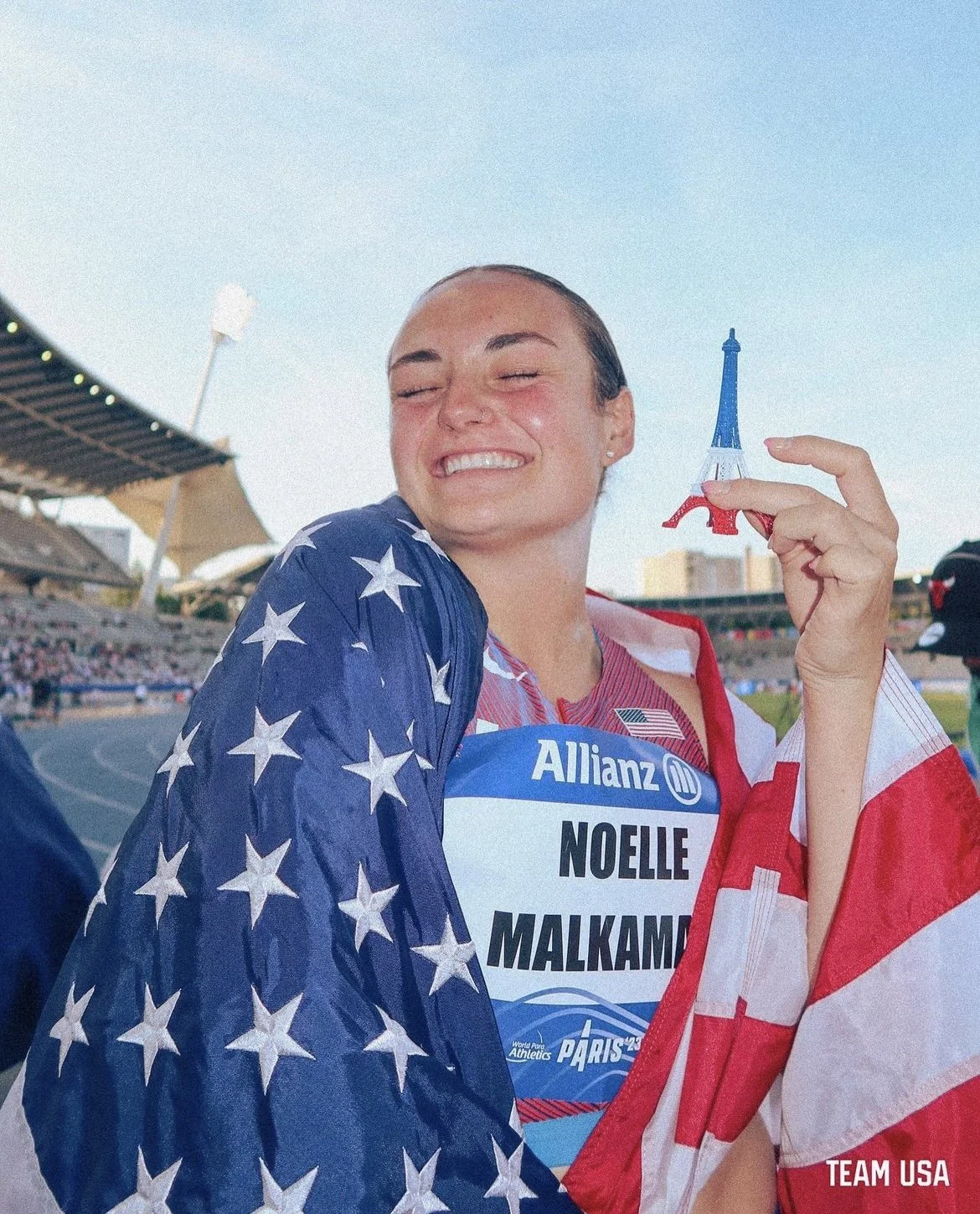

I became a member of Team USA in July of 2022. Since then I have won three gold medals: one at the Paris, France 2023 World Championships, one at the 2024 Kobe, Japan World Championships, and my most recent at the 2024 Paris Paralympics where I broke my own world record with a throw of 14.06 meters in the F46 Women's Shot Put.

Working my way up from being the worst thrower on my college team to recording top-ten all time program marks in shot put, discus, and the hammer throw wasn’t easy. Working my way through resistance to my identity as a disabled athlete to being able to accept myself as I was and chase a new dream also wasn’t easy. But I don’t think we should make our decisions based on doing what’s easy.